Twitter: Removing Share Counts to Increase Share Price?

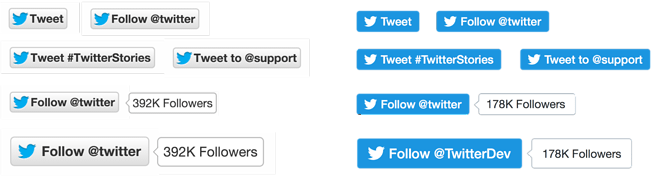

Twitter announced recently that they are going to close down the API that provides share counts for webpages.

This means that share buttons (like the one above) will no longer display counts, and tools (like URL Profiler) will no longer be able to report on Twitter share counts.

It’s fair to say that a lot of people are pissed off about it. You can read them ranting in the comments on the developer blog or on this (rather angry) reaction post.

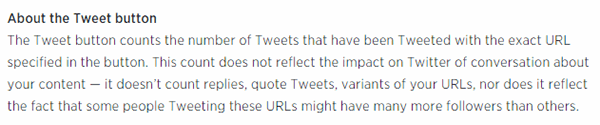

Twitter published a post on their developer blog that explained why they have decided to do this. In amongst some technical and financial considerations, they claim that:

Effectively, they are saying that Twitter share count is a shitty metric.

Are Social Share Counts Bad Metrics?

So, according to Twitter, their share count relates only to tweets or retweets of the exact URL, and all tweets are equal.

Let’s face it, this does make the data incredibly gameable.

In a more legitimate manner, it is common practice to tweet out the same URL/message multiple times, in order to hit users in various different timezones.

You can also use tools like IFTTT to automate tweets if you have messages you wish to share regularly.

Every time 2pm on a Tuesday rolls around, score one more for me on the tweet counter.

This sort of practice is pretty common, and definitely shows that tweet count is not a perfect metric by any means.. But we all sort of knew that anyway, right?

I think it is less common knowledge how the other big players calculate their share counts.

Google+

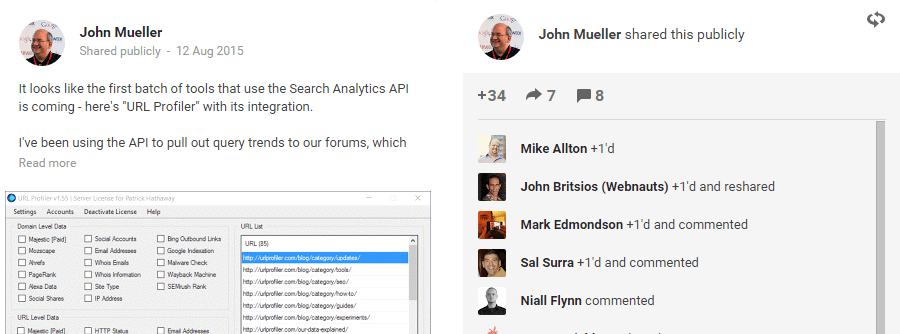

In an effort to seem less shit, it seems that Google’s flailing social network deliberately pumps up their numbers by making any interaction count on their counters.

The ‘plus 1’ count is a rather sketchy combination: the number of times the URL has been had the +1 button clicked, plus the number of times the URL has been shared/reshared on Google+, plus any +1 of those shares or comments.

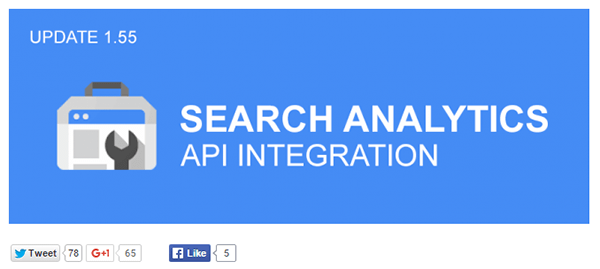

Here’s an example – our update post when we launched Search Analytics integration.

See the 65 +1s? Most of those came all at once, after John Mueller shared the post on Google+

Call me ungrateful, but those don’t really feel like individual +1s. They certainly don’t represent 65 different people clicking the +1 button, which is sort of what you feel like its meant to be counting.

As the pre-eminent powerhouse of social media, you would have thought Facebook wouldn’t need to pull any fast ones here (whereas Google+, well…).

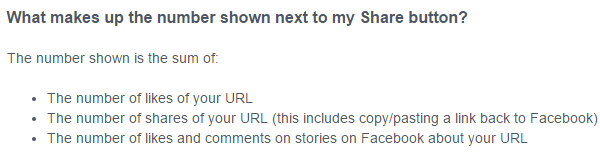

Yet, here’s how they define their share count in the developer area:

The third point is the most cryptic. So someone posts an update (story) on Facebook, which includes your URL, and any likes or comments will get counted in their ‘like’ count.

Seems a bit wishy washy to me.

And what happens when we are all yaying, wowing and angrying?

Are we really going to have share counts for all of them?

Apples to Oranges

The problem with sharing buttons as they are usually laid out is that the implicit assumption is for the counts to be equivalent.

As we have seen, this is not the case. So maybe we can accept the point that these metrics are not particularly good at actually measuring anything.

But does that make them useless?

People Care About Share Counts (Because…)

I don’t think they are useless – simply because people care about them.

Because they help you separate the wheat from the chaff

However shitty a metric share count is, at least it gives you an indication whether people like your stuff or not.

We know a bit about this one, since content auditing is one of the primary use-cases of URL Profiler, and social shares are a pretty standard metric that our users take into account. Social shares give you an idea of which web pages have gained social traction, and (often more importantly), which have not.

Knowing which pages on your website have received no social interaction can help you decide which content to cull, while auditing. Similarly, pages with a lot of shares indicate that you’ve hit upon a topic that has resonated with your audience. While looking for inspiration on content creation, share counts are a straightforward indicator of successful content.

If Twitter really cared about their users having access to accurate data, they’d build “Twitter Webmaster Tools”, where you could associate your account with a domain and then access page level insights on shares and engagement.

Because you can point to them and say, “I did that”

Share counts are often dubbed ‘vanity metrics’, as if they have no intrinsic value, neatly missing the point that ‘vanity’ is a form of self perception. Behind every piece of content shared on the web is an author or creator, who, like everyone, has motivational needs.

Studies into motivation show that one of the strongest motives is purpose – we want to do things that matter, that are significant – that make a contribution.

High share counts can make you feel like you’ve made a contribution, and because they are visible, others can see that you’ve made a contribution, which also plays into your sense of purpose.

Beyond the squishy feeling of wellbeing, this could also hit some bloggers in the pocket. Bloggers that work with brands to help promote them to the masses can no longer point to their share counts and say ‘Look, I iz well good at Twitter.’

Similarly, marketing teams looking to evidence their success may have to look into other ways to secure executive buy-in on their campaigns.

Because they encourage sharing

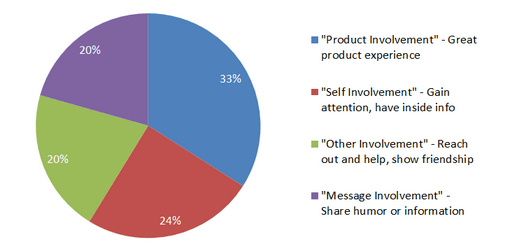

Studies into why people share show that the reason that people share content has a lot to do with self-fulfilment. Among other things, ‘sharers’ feel that the content they share helps to define themselves to others, and they want to share information that others will find entertaining or valuable.

Share counts can also provide social proof, which helps readers judge the ‘value’ of content and whether it is worth them sharing it (heaven forbid you share something that others think is ‘only ok’).

Of course, this type of thinking can also lead to ‘blind tweeting’, where readers share articles without actually even reading them.

A Slap In The Face

So, yes, tweet count is a metric of dubious quality, but people care about it anyway. The fact that Twitter know this and are removing it anyway feels like a bit of slap in the face for the community which supported its growth.

Lest we not forget that many of Twitter’s core interactions – such as hashtags, retweets and @mentions – were originally developed by users of the platform, and then later formally adopted by Twitter and built into the UI.

how do you feel about using # (pound) for groups. As in #barcamp [msg]?

— ⍨ Chris Messina ⍨ (@chrismessina) August 23, 2007

Similarly, before Twitter officially launched their Tweet button in August 2010, everybody used the 3rd party ‘retweet’ button by Tweetmeme (now defunct), which displayed its own counter.

Now I Ain’t Sayin’ She a Gold Digger…

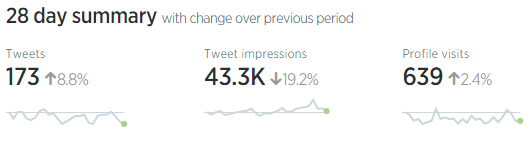

Some commentators have argued that Twitter’s motive is to encourage more users to login to the Twitter app and access Twitter Analytics, where they can attempt to sell ads to you.

Whilst I’m sure many users would actually welcome share data per URL in Twitter Analytics, there is nothing even close to that in the platform right now. The data is instead segregated per tweet, follower, ad, card, video, etc…

According to Twitter, the depreciation of the Twitter Count API actually marks the culmination of a much deeper plan for their API and infrastructure. Twitter are finally completing the process of migrating away from their current database (‘Cassandra’) to their new, real-time, distributed database (‘Manhattan’).

According to Twitter, the depreciation of the Twitter Count API actually marks the culmination of a much deeper plan for their API and infrastructure. Twitter are finally completing the process of migrating away from their current database (‘Cassandra’) to their new, real-time, distributed database (‘Manhattan’).

The tweet count feature exists on Cassandra, and so effectively their decision is to not rebuild it on Manhattan.

But if you are moving over to a new infrastructure, why would you deliberately make it worse?

But She Ain’t Messin’ With No Broke…

The only logical answer is that they don’t want to pay to support it. The bandwidth of every blog on the internet requesting data from them all the time must add up to a pretty significant burden – for a feature that has no potential to ever make them money.

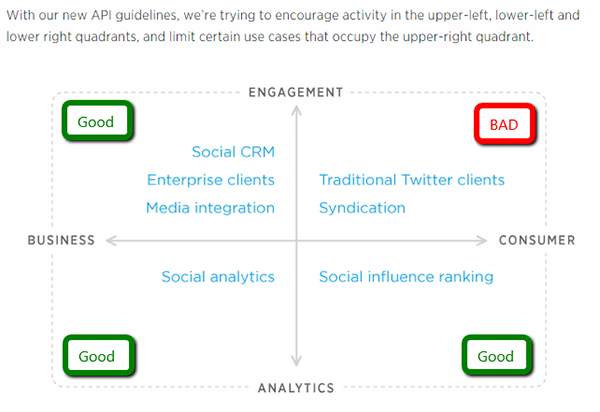

In the past they have demonstrated their intent with the API to make it more business-focused, which looks set to continue now. Here is an extract (notations mine) from their 2012 announcement post of version 1.1 of their API:  Take a guess where ‘Share Counts’ fits on that graph? You guessed it – top right.

Take a guess where ‘Share Counts’ fits on that graph? You guessed it – top right.

They don’t want to encourage that stuff because it’s not where the money is. The money is in business applications, not bloggers.

Instead of a free-to-all unsupported API endpoint, you can buy the data from Gnip, the social platform that Twitter acquired last year. We reached out to them to find out if we could get the data we wanted, but they don’t have it either (remember, Twitter decided not to rebuild it) – the most they can give you is 30 days worth. For $3000-$5000 a month, paid annually.

So, yeah, the money is in business applications.

It looks like this is just the tip of the iceberg, however, as Twitter are trimming the fat from other areas of their business too, having just unceremoniously culled 8% of their workforce.

I’ve been impacted by $TWTR‘s layoffs. This is how I found out this morning. pic.twitter.com/MbjFwYLcU2 — Bart Teeuwisse (@bartt) October 13, 2015

Twitter have clearly had to make some hard decisions, because ultimately, as a public company, they are accountable to their shareholders.

Unfortunately for us, it doesn’t matter how useful we might think share counts are, as Twitter is focused on an entirely different metric – their share price.